Class C schools, Class C tournaments, Class C towns.

What does that C stand for? According to the Montana High School

Association, Class C designates the high schools with fewer than 120 students.

In Montana, that's about 64% of all high schools. 108 of them, to be exact,

located in tiny towns and reservation communities across the state.

Jocko Valley, home of Class C Arlee High School

In towns with Class C schools, the school functions as the pivot

point for many activities. Even folks without kids in school come to school

events such as band concerts and fundraisers. Grandparents, aunties and uncles

and other extended relatives fill the seats at athletic competitions and

graduations. Even some funerals are held in school gyms, when there is no other

venue large enough.

And when Class C schools travel, towns empty out. "Last one

to leave turns out the lights" goes the saying. Here's a Missoulian article about this phenomenon from last year's state basketball tournament. And what about those fans? Here's what the Northern Sports Network reported when Arlee's eight-man

football team made it to the state championships for the first time 29

years: "The fans were one of the notable parts of the game.

Hundreds of fans made the 366 mile trip to Chinook to watch their team play in

the title game."

Three hundred and sixty-six miles. That's over five hours one

way. Yes, Montana, but also yes, dedication. Can you see the caravan of

cars, painted red and white, stretching for miles across the plains, heading

east to watch their team - our team - play in their first state championship in

decades? We lost. But here's what happened then: "Following the trophy

presentation, the Arlee players lined up single file and every single Warriors

fan came by and gave each and every player a hug. The emotional event lasted

over 45 minutes." Because that's how we do.

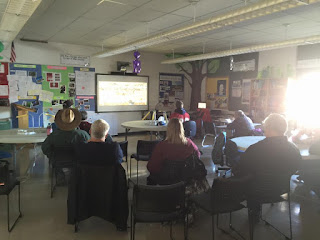

Community members left behind watch the game from a high school

classroom.

When Class C Chinook lost a wrestler in a car accident just before the state tournament earlier this month, Arlee distributed memorial armbands to their wrestling team. One Chinook wrestler remarked, "It just shows that the whole wrestling community is one big family." The wrestling community and the community of small towns: one big family. That's how we are.

And of course last night at the Western C Divisionals basketball

tournament in Hamilton, 72 miles away, hundreds of Arlee fans packed the gym to

watch both of their teams compete in the championship games. Picture this: One

side of a gymnasium fully wearing red. Half of the opposing bleachers, also in

red. One full end, also in red. This crowd is rowdy, ready, loud, and

proud. Not only did both teams bring home the first place hardware and

clinch a trip to state, the girls became the first team in recent memory to do

so.

Around 11:30, I was home enjoying some couch time when I heard

the sirens. Not fast, but slow. Not one, but several. And the honking. I

stepped onto the porch, and cue the goosebumps - the teams were back from the divisional tournament,

escorted by our town's emergency vehicles, flanked by happy parents

and grandparents and aunties and uncles and extended family.

If you do not live in a small town, you cannot know the elation

of a community that rallies around its own: the gyms packed with

sports fans, proud parents of graduates, or mourners at a funeral.

If you do not live in a small town, you may not "get"

the excitement of caravans that travel together, hotels full of guests who know

each other, hundreds of fans with matching t-shirts in faraway bleachers.

If you do not live in a small town, you may not guess what the C

in Class C really stands for: community.