Dear Pre-Service and Early-Career Teachers:

Recently I finished the semester at the University of Montana where I have spent four years as an adjunct. I can describe the attitude most of you pre-service teachers have toward your new career: cautious idealism. You have some sense that the job ahead will be difficult yet gratifying, poorly compensated yet rewarding. And you are amenable to the drawbacks because the returns are so great.

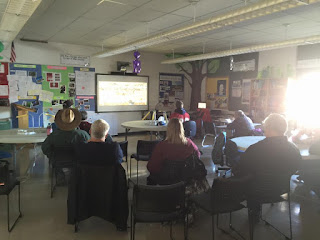

Pre-service teachers learning about Twitter in my media literacy methods course

What you don’t yet know about yourselves is that although you may become wonderful teachers, most of you are humble. Although you may become true professionals, many of you will not become teacher leaders. Although you will advocate for your students, you will not often use your voice for yourselves.

I know you. You are teachers, and it is in the nature of teachers to serve and support others wholly and selflessly. It is almost antithetical for teachers to advocate for ourselves. We do not know how to talk to others about our work or our successes, and we certainly don’t feel comfortable asking for support.

Despite all its best intentions, Teacher Appreciation Week reinforces this notion that teachers should quietly and humbly accept our gifts and discounts for a week. It says, “please take this latte from the PTO since we all know you’re not getting a raise this year.” It says, “let us recognize these professionals who help raise the nation’s children and forget for a few days how policies often undermine their agency.” It says, “teachers are martyrs who sacrifice everything, including themselves.”

On Teacher Appreciation Day I received two lifesaver candies in my mailbox from an administrator. I choose to see one candy as a metaphor for my work with kids (a total overstatement, in most cases) and the other as a metaphor for self-advocacy. And it's not ironic that I, myself, am wielding the second lifesaver, for myself.

I would love to trade the candies and coupons for a raise and recognition of my profession as such. But here, here is the place of tension: advocating for ourselves belies our very nature and desire for humility. The attitude I want to cultivate feels self-serving. How does one ask for more, when one is advised by the inner counselor to be satisfied with less?

This inner counselor came to mind as I listened to you, my pre-service teachers, struggle on the last day of class with the mock interview question, “Why should we hire you?” One after the other you said you didn’t feel right "bragging." I chided, “You have to get over this feeling. You serve others, but you cannot do so effectively if you are meek about your career choice. You are your own best advocate, and when you speak for yourselves, you lift up the whole profession!”

With that small pep lecture, I hope to plant a seed of agency inside you, new teachers. I hope as you move into your careers, you will hear the rising voices inviting you to join teacher leadership. Above all, I hope you will lift your own voice as a professional, knowing that your work and your commitment are worthy of respect – both from others and from yourself.

Teachers at Teach to Lead Summit in New Orleans, where teacher leadership ideas take shape